Precious Metals

Home / Reports / Materiality reports

Materiality summary

While the depreciation of the rand has improved the competitiveness of South Africa’s labour over the past years, the South African mining industry is nonetheless faced with uncomfortable truths that expose the traditional high-labour business model as being uncompetitive in the modern era. The mining industry spends 80% less on technology and innovation than the petroleum industry, for example.

Smart technology and mechanisation are providing competitors in other countries with major advantages, including: faster lead times and more flexible response, higher recovery rates, better identification of available ore seams, higher productivity and better safety records.

The imperative for South African mines to invest in technology and mechanisation is unavoidable, especially as SA ore reserves are now to be found at ever deeper levels, or require more advanced techniques to extract product from lower ore grades. Already, 30% of SA’s platinum now comes from mechanised mines.

If gold and platinum mines continue as before, they will simply go out of business (rationalisation continues with Amplats exiting Union and Rustenberg mines). In order to build the capacity to become profitable in the long term, SA mining companies will have to invest in smart technology and mechanisation. This is already starting, Amplats’ modernised Batophele mine being an example.

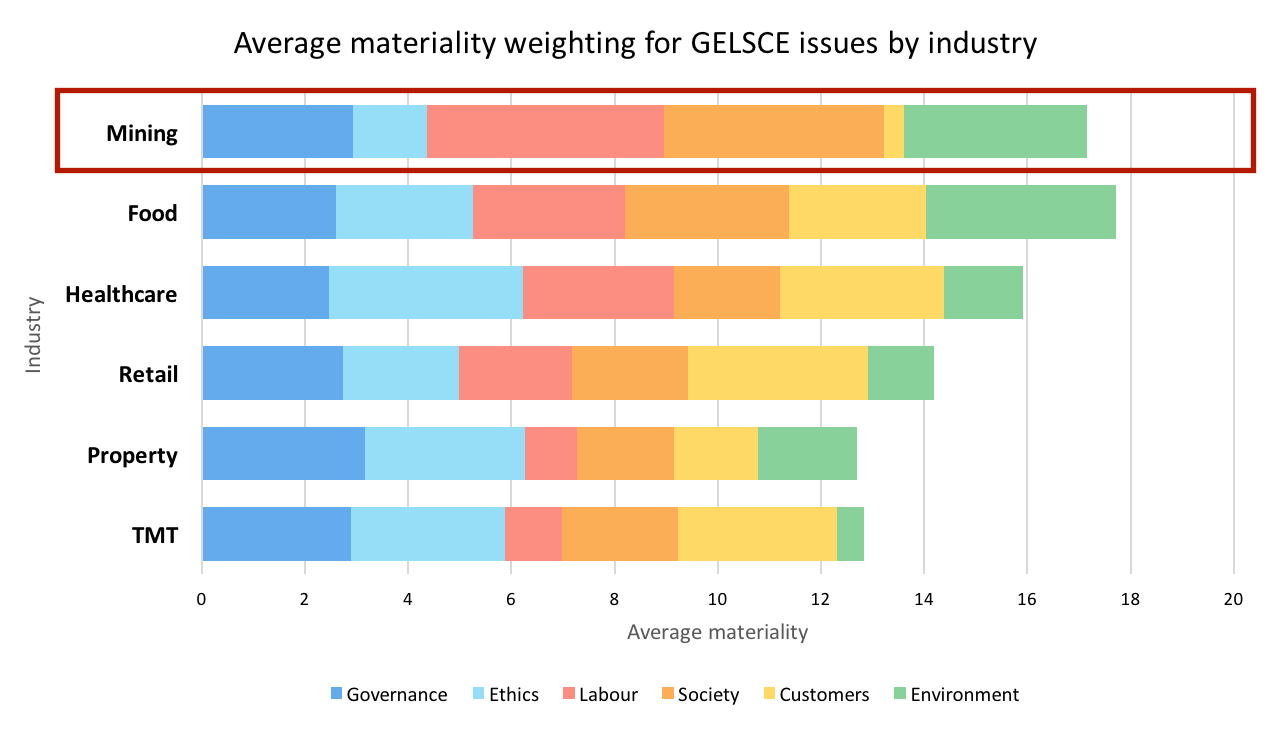

In our view, the most material non-financial, or underlying ESG issues for the mining industry is how to deal with the expectations of surrounding communities in the face of the new reality of mechanisation and thus fewer jobs.

Our view is that Gold Fields’ diverse assets in other geographies and its strategy of diverting its investment away from non-performing assets in South Africa, is a valid and responsible reaction to this issue as it reduces the residual risk it faces. Nonetheless, South Deep is a significant asset. Despite strong acknowledgement of the challenges facing community development by CEO Nick Holland, a clear strategy has yet to emerge.

Amplats, as PMG metals producer, is more wedded to the Bushveld Complex, and thus to South Africa. Consequently, its exposure to the risks associated with this issue are higher. And its reporting reflects a more mature leadership approach to community development than does Gold Fields’. Amplats not only invests R&D in Fuel Cell technology and in the local jewellery industry, but also shows real commitment to local enterprise development, particularly related to its own supply chain. Whether the former will materialise and the extent to which the latter will make a significant impact on the local economy, remains to be seen.

Labour

Fair labour

The Platinum miners’ strike of 2014 was a result of poor stewardship by mining leadership of its human resource capital. During the platinum metal boom of the previous period, the gap between executive management earnings and mine wages rose to unsustainable levels. Meanwhile, the Farlham Commission revealed the financial difficulties facing miners in the form of garnishee orders that rendered many of them impoverished on pay day. Mechanisation and the mining exodus from South Africa further put further pressure on employment levels. In particular, mines will continue to shed jobs as they accelerate towards a smart-tech, mechanised and more labour efficient model of mining ores further out of reach of traditional methods. These and other challenges have to be addressed by mining houses in the rebuilding of relations between mine management and workers post Marikana.

Gold Fields experienced a foretaste of this. Its initiative to bring in an Australian team to lead mechanisation at South Deep was, by its own admission) a disaster, meeting strong political resistance.

Artisanal and illegal mining

An emerging issue addressed by very few companies in the analysis is that of artisanal and illegal mining. This is but one expression of the frustration shown by local residents in being shut out of the apparent riches being exploited by foreign miners. The mining industry needs to find ways to include marginalised operators, whether at the informal, low-technology level, or at a higher, more formalised level.

Society

Community expectations

The hard realities facing the labour-serving communities in the mining belt has yet to hit home, and expectations of jobs are wildly unrealistic. Communities have high expectations for development, leading to rapid influx into local towns (Greater Tubatse’s population, for example has increased from 260,000 to 375,000 since 2006). Workers seeking employment, or recently retrenched, begin venting their anger against preferential treatment given to those still in employment.

Smaller workforces will require new models for engagement with communities. Current mining CSI programmes are inadequate for they have failed to encourage local economic development for self-reliance.

LED in partnership with local government

On the other hand, local municipalities’ budgets are too small to provide the infrastructure required for the growth of the local economy (roads, housing, water & sanitation, electricity, schooling, etc.). Private/public partnerships will need to be further strengthened to develop local infrastructure, hopefully implementing projects that offer direct benefits to mine and community.

Environment

Downstream beneficiation

Likewise, there is growing realisation that local economic investment in downstream beneficiation of the primary mined product would be a way to develop the local economy rather than sending commodities offshore for others to benefit from adding value. The platinum industry is showing signs of interest in this arena, developing fuel cell technology to augment alternative energy systems, as well as catalytic converters to meet tightening environmental legislation to reduce vehicle exhaust emissions. Other industrial opportunities beckon, as well as the jewellery industry, thus far with little success.